Thinking beyond Sustainability

Tipu Ake to Kaitiakitanga

A presentaion by Andree Mathieu a physicist, researcher, thinker and writer from Quebec, to the NZ Association of Accountants ACANZ Sustainability Group meeting 10th March 2004.

For many people, sustainability translates into being “environmentally friendly”, but it is broader than that. Understanding and adopting sustainable business practices requires a new awareness of the world: the whole world, its natural systems and all of its species. It requires a deeper understanding of how the Earth works, how man’s processes affect nature’s delicate balance and how our actions will ultimately affect our children and the children of all species.

Interface Inc. is the world’s leading commercial carpet and interior fabrics manufacturer.

For Interface and the Forum for the Future, sustainability is:

“A dynamic process which enables all people to realize their potential and to improve their quality of life in ways that simultaneously protect and enhance the Earth’s life support systems”.

Interface strives to become a restorative enterprise “putting back more than it takes and doing good to Earth – not just no harm – by helping or influencing others to reach towards sustainability”. To do this, they need a compass to guide them through their journey and to help them understand how everything they do, everything they take, everything they make and everything they waste affect nature’s balance.

The Natural Step: a compass to guide us in our journey towards sustainability:

The Natural Step is an international non-profit advisory and research organization working to accelerate global sustainability. It was started in 1989 under the leadership of the Swedish cancer physician Dr. Karl-Henrik Robèrt. In the course of his review of literature pertaining to health-related effects of environmental contamination, Dr. Robèrt became aware that effective action on environmental problems was being held back by endless disagreement over details. This insight convince him that what was needed was a way to address environmental issues as an entire system rather than as a series of disparate symptoms. As a cellular biologist, Robèrt knew that certain fundamental requirements must be met if a cell is to survive; similarly, he hoped that the scientific community in Sweden could reach consensus on the fundamental conditions for a sustainable relationship between human society and the rest of nature. Towards that end, Robèrt facilitated a consensus process that resulted in many of Sweden’s leading scientists agreeing on the essential scientific principle that define the basic requisites for life on this planet. Out of these scientific principles derived four statements of eminent common sense that together form a unique and easily understood compass towards a sustainable future.

For The Natural Step, sustainability is fundamentally about maintaining human life on the planet and, thus, meeting human needs worldwide is an essential element of creating a sustainable society.

The other three principles focus on interactions between humans and the planet. They are based on science and supported by the analyses that ecosystem functions and processes are altered when:

Society mines and disperses materials at a faster rate than they are re-deposited back into the Earth’s crust (examples of these materials are oil, coal and metals such as mercury and lead);

Society produces substances faster than they can be broken down by natural processes, if they can be broken down at all (examples of such substances include dioxins, DDT and PCBs); and

Society depletes or degrades resources at a faster rate than they are replenished (for example, over-harvesting trees or fishes), or by other forms of ecosystem manipulation (for example, paving over fertile land or causing soil erosion).

Then, The Natural Step’s sustainability principles, also known as the “minimum conditions” that must be met in order to have a sustainable society, are as follows:

In a sustainable society, nature is not subject to systematically increasing:

1. concentrations of substances extracted from the Earth’s crust;

2. concentrations of substances produced by society;

3. degradation by physical means; and, in that society…

4. human needs are met worldwide.

Backcasting: how to stay focused on the desired outcomes

The most common way of planning for the future, in most environmental programs, is to review the present state, starting with a list of negative impacts in nature that have already been discovered, and then try to remedy these problems in the future. We call this forecasting. With a pressing need for fundamental change and a high level of complexity, this planning technique has many disadvantages. Perhaps its most crucial flaw is that whatever seems important in the present comes to define the future. Incremental changes of an old system can sometimes be counterproductive, even if they are to reduce today’s impact in nature, and it can also lock up resources.

The TNS Framework is based upon a method known as backcasting – looking at the current situation from a future perspective. Initially, you envisage a successful result in the sustainable future scenario; then you ask: “What can we do today to reach that result?” Using backcasting, in line with the minimum conditions, allows you to make sure that your actions and strategy are taking you in the direction that you wish to head and that they align with your vision.

The TNS Framework is applied in four major steps:

A. Building common awareness and understanding while discussing the TNS principles among all participants and align behind the sustainability objectives;

Interface engaged key players in the global environmental effort to help them prioritise challenges and opportunities, resulting in the creation of a dynamic advisory team.

They implemented QUEST (Quality Using Employee Suggestions and Teamwork), a worldwide initiative focused on identifying, measuring and eliminating waste at a local scale, and sharing the knowledge for global application and results.

They held a “Greening the Supply Chain” conference where suppliers’ technical personnel were exposed to Ray Anderson’s vision of sustainability and were asked to join him on Interface’s journey. They were asked to build new partnerships with Interface by creating innovative ways of supplying her with environmentally conscious products.

They held their first ever World Meeting, designed to bring together the diverse international businesses of Interface and to create a shared understanding of sustainability. They brought together global associates from 34 countries on 6 continents and created important connectivity to prepare them for their journey.

They created the Interface Sustainability Report, the first publication of its kind. Although there are many corporate environmental reports, as far as we know, this was the first corporate sustainability report and the web site is the follow-up to that first report.

B. Conducting a baseline assessment (major flows and impacts):

What does your organisation look like today?

Where you are.

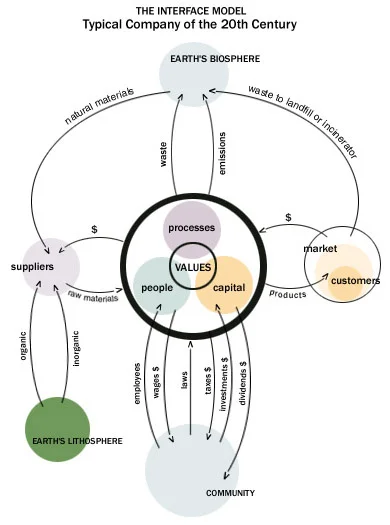

from www.interfacesustainability.com/model.html

C. Creating a vision:

What does your organisation look like in a sustainable society?

Where you want to be.

Interface is committed to shifting from linear industrial processes (take – make – (downcycle) – waste) to cyclical ones.

from www.interfacesustainability.com/model.html

List all measures, wether or not they are realistic in the short term;

What would need to be in place there (outcomes)?

D. Advising and supporting the execution of specific initiatives (projects, outputs) by providing appropriate training, techniques and tools for implementation

Followed by measuring progress (indicators) towards goals and suggesting modifications as needed. How we will know we are close.

At the core of Interface’s sustainability efforts is a measurement system developed by IRC (R&D branch) that enables them to understand their impact and change their behaviour. Each Interface business unit monitors its monthly material and energy flows on an EcoMetrics scorecard. At the facility level, the metrics are very specific and detailed (outputs). But at the corporate level, these numbers are used as indicators that help to answer the question “Is Interface making progress in its quest to achieve its sustainable future scenario?” (outcomes).

They have shared their model, set of goals and metric systems with countless other companies and organisations like certifying organisations, evaluating organisations, standard setting organisations or environment management systems (ISO 14001), testing protocols, rating systems (LEED), performance tracking and reporting organisations.

Sustainability through courageous innovation -

Our credibility has been formed through the eyes of others

“A kumara never calls itself sweet, that's for the eaters to say”

A Maori proverb often heard at Te Whaiti

Interface prides itself not only in sustaining the company, but also in sustaining jobs and families. Interface actively seeks ways to incorporate more family time into employee's schedules, as well as ways to transfer the company's ideas and knowledge about sustainability into people's everyday lives.

The social elements of sustainability at Interface Inc. are vast, and cover many aspects of business operations from employees, suppliers, investors, stakeholders and customers to the communities where her facilities are located. Interface Research Corporation (IRC) has begun to focus on organizing, understanding and measuring their continual growth in social sustainability. Measuring the social impacts of sustainability at a company includes both quantitative and qualitative measurement. To be most effective, there must be a unified process of pulling together this information. Interface has developed a set of “soft” dialogue processes with different stakeholder groups and a set of “hard” internal measurements to help them understand where they need to target their improvements. The latter are called SocioMetrics and use a consensus-based process. This global effort will allow all of Interface's business units to share, learn, develop, improve and coordinate practices, programs and initiatives surrounding social sustainability throughout the company.

With The Natural Step providing a compass to steer a company in the direction of sustainability, a company's management system can move from a focus on compliance and incremental improvement to a focus on creating a better bottom line and a sustainable, or even restorative, economy. Together, they form an excellent pair of planning and implementation tools for business. Moreover, from a strategic point of view, backcasting allows you to deal with the complexity of today's world in a far more effective manner than forecasting. It allows you to create solutions that focus on the outcomes you desire rather than trying to tackle the myriad problems. In short, it allows environmental and social problems to be turned from a potential major liability into a potential major opportunity.

The philosophy of Tipu Ake ki te Ora and Kaitiakitanga

The skills required to turn a potential liability into a potential opportunity: focus on the general outcomes instead of just the measurable outsets, backcasting from a future perspective, shared knowledge and experience, shared leadership, are what attracted me to New Zealand. When I was introduced to the Tipu Ake Project Leadership Model for Innovative Organisations, I could not help but notice the similarities in the mindset of the Maoris at Te Whaiti and that of Interface and The Natural Step.

Tipu Ake ki te Ora (growing from within ever upwards towards wellbeing) is a Lifecycle. Let us summarize how the Interface's transformation relates to the Tipu Ake model.

0 Undercurrents: Ray C. Anderson was sent to the undercurrents when he was asked to speak about Interface's environmental policy and found out that it was to comply with the laws. It set “action stations” in the company and that's when they made their “mid-course” correction.

1 Leadership: Ray Anderson is a courageous “bird”. He took the seed of “becoming a sustainable industrial enterprise” and gathered together a team of key players in the global environmental effort to share their knowledge and draw Interface a route towards sustainability.2 Teamwork: Interface implemented a project called QUEST implying all the Interface employees worldwide in a zero-waste initiative. They held a conference where suppliers' technical personnel were asked to join Interface on her journey and create innovative ways of supplying her with environmentally and socially conscious products. They held a world meeting to create a shared understanding of sustainability amongst the diverse international businesses of Interface. They created the Interface Sustainability Report to share their journey with all their stakeholders (clients, communities, etc.) including their competitors.

3 Processes: Interface is redesigning her products and processes to epitomize her vision. It includes “closing the loop” or “cradle to cradle” design and “biomimicry”, using Nature as the ultimate teacher.

4 Sensing: Interface created her own measurement system to continually monitor her progress towards the realization of her vision. They also seek the evaluation of several global organisations (ISO, GRI, PEE, etc) and put all the results into perspective to check if their behaviour is leading them in the right direction. The measurement is both quantitative and qualitative: it includes “hard” internal indicators but also “soft” dialogue processes that allow a sensibility check over the process level. In the language of Tipu Ake, that sensitivity “hook-up” is “a wisdom-based gathering of information that focuses on building a collective view from all individual perceptions”.

5 Wisdom: In her journey towards social and environmental sustainability, Interface is growing a collective “intellectual capital” that is much more than just knowledge. It is the integration of all the diverse learnings, reflections, experiences, sharing, emotions and beliefs gathered through the journey.

N Wellbeing: This level is about “meaning”. It is what drove the people in Te Whaiti when they transformed their school. It is what is still driving them in their Kaitiakitanga program to transfer to the children of Te Whaiti the responsibility to treasure the Whirinaki forest and their culture. It is related to the holistic Maori concept of Ora and the philosophy of Kaitiakitanga. I came in New Zealand to go further into the worldview that sustains these concepts and to write about it. It is a similar mindset that lies behind the efforts that Interface puts into pursuing her vision for the sake of all the children present and future.

Websites:

www.interfacesustainability.com

www.naturalstep.org

www.tipuake.org.nz

www.kaitiakitanga.net

This reflection is Andrée Mathieu’s koha (gift in return) to the Maori people of Aotearoa and in particular the Ngati Whare and other people of Whirinaki, Te Urewera who have shared much with her. She has assigned the copyright of this work to their home, the place Te Whaiti Nui-a-Toi, the sacred store place of their ancestral wisdom for around 1000 years. Here it will be safe guarded and freely shared for the benefit of all the world's future grandchildrens. With the permission of the author and inclusion of the copyright statement it can be freely published.

The Tipu Ake Lifecycle - A leadership model for innovative organisations. (c) 2001/2 Te Whaiti Nui-a-Toi, see www.tipuake.org.nz In the knowledge sharing tradition of Toi the Tipu Ake Lifecycle is in shared with the world to be used for the wellbeing of its future chldren. In return a koha (gift you can afford based on its value to you) to help further voluntary education and community development in the valley and beyond is appreciated.